Can Smartphones Help Patients with Behavioral Health Disorders?

eHealthcare Pulse

// By Jane Weber Brubaker //

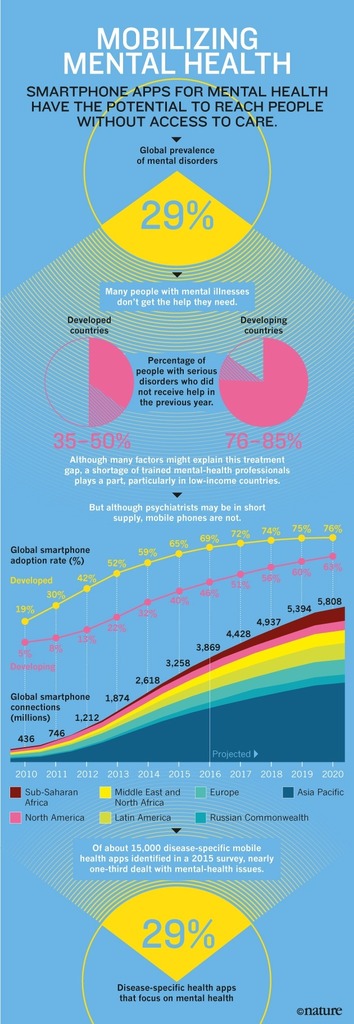

“One in four Americans experiences a mental illness or substance abuse disorder each year, and the majority also has a comorbid physical health condition,” says the American Hospital Association (AHA). Treating mental illness contributes significantly to overall healthcare costs. Health Affairs reported last year that Americans spent more on mental disorders than any other medical condition in 2013—a whopping $201 billion.

“One in four Americans experiences a mental illness or substance abuse disorder each year, and the majority also has a comorbid physical health condition,” says the American Hospital Association (AHA). Treating mental illness contributes significantly to overall healthcare costs. Health Affairs reported last year that Americans spent more on mental disorders than any other medical condition in 2013—a whopping $201 billion.

Is there a role for digital technologies in diagnosing and treating mental illnesses? Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) is investigating how data from smartphones could shed light on what happens between visits to the clinic.

John Torous, co-director of the Digital Psychiatry Program at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center

“Using smartphones and people’s personal devices and sensors to collect information and learn about mental health wasn’t a very big field or active research area four or five years ago,” says John Torous, co-director of the digital psychiatry program at BIDMC, a Harvard Medical School-affiliated teaching hospital, where he also serves as a staff psychiatrist and clinical informatics fellow. “There was actually this belief that people with mental illness or psychiatric conditions didn’t own technology or want to use technology as part of their healthcare.”

Both assumptions proved to be incorrect. “We did a pretty simple study of patients in the psychiatry clinic. We just said, ‘Do you own a smart phone? And are you interested in apps for mental health?'” says Torous. The response was overwhelmingly positive from patients. “So we realized that perhaps there was an unmet need or an untapped potential in this space.”

Health systems have gotten better at coordinating care and helping patients manage chronic diseases. But physical health is not the whole picture. How can providers begin to address both the physical and mental health of patients? Can technology help?

Here, we’ll explore how researchers at BIDMC and Harvard School of Public Health are tapping into new data streams that paint a much more detailed picture of patients’ lives between clinic visits. We’ll also take a look at behavioral health apps for consumers—a category that is growing fast—and a framework to evaluate them. How are you guiding your patients to the right tools to optimize their whole health?

Active and Passive Data Paint a Detailed Picture

Once Torous and the Digital Psychiatry Program discovered patients were interested, they began by putting assessments onto consenting patients’ smartphones to measure depression, and collected data daily. “Our question was, ‘How does a scale that you take in person with a clinician monthly compare to an average taken over 30 days?’” says Torous. The answers were quite different. “When you’re with the stressors of being at home, being at work, depending on time of day, we found that mood just varies a lot more.”

Taking it a step further, Torous is collaborating with JP Onnela, assistant professor in the department of biostatistics at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, on a project to collect “passive data” from consenting patients’ smartphones. A survey collects active data when the patient answers questions, self-reporting information about his or her health or activities. Passive data, by contrast, is collected from a patient’s usage of the phone, and measures discrete activities such as:

- GPS feed

- Accelerometer

- Anonymized call and text log

- When the phone is charging

- When the screen is on or off

- Voice samples (with user consent)

Your Phone Knows How You Feel

A post on the Harvard School of Public Health website, “Your Phone Knows How You Feel,” illustrates how passive data can shed light on patient behavior. The example is a fictitious patient with bipolar disorder:

On a difficult day, the patient’s data stream includes very few pings. Her GPS sensor shows her going slowly from the bedroom to the bathroom and back again. She does not check email, but does watch four hours of Netflix. No phone calls out, except for Chinese food. Seven phone calls in, from her sister. She answers none of them.

On a high day, her data stream shows jerky movements all over the house, plus 12 trips outside, including two to the liquor store. Twenty-five calls to people very low on her contact list—some of whom she hasn’t spoken to since high school. Three hours of sleep. And $3,000 spent via PayPal on Etsy.

“We’re getting a very detailed snapshot of what their behavior is on a minute-by-minute scale,” says Torous. “The question now is to figure out what in that sea of data is useful.”

Vision for Diagnosis and Intervention

Torous envisions two uses for the data, one on the diagnostic side, and the other on the intervention side. “The hope is, once we have these new data streams from digital technology and understand them, we can better stratify, categorize, and understand different subtypes of mental illness,” he says. “What is it that someone is experiencing, and what type of mental illness is it?”

On the intervention side, the smartphone is capable of pushing interventions through apps. “We’re seeing apps being pushed that can deliver different therapies, especially cognitive behavioral therapy,” says Torous. “We’re seeing apps that can help people manage their psychiatric medications, or encourage a healthy lifestyle habit like diet, exercise, and sleep that are frontline treatments for many mental illnesses and can benefit many people.”

Good Apps, Bad Apps

The problem is, how do patients pick the right app? Jennifer Nicholas, a researcher at the Black Dog Institute in Australia, studied apps for bipolar disorder (BD) and discovered that some were not only incorrect, but they were giving dangerous advice. “The app was telling people to drink hard alcohol if they were entering a manic episode,” says Torous. “Another recommended that people in a depressive phase of bipolar avoid contact with family and friends.”

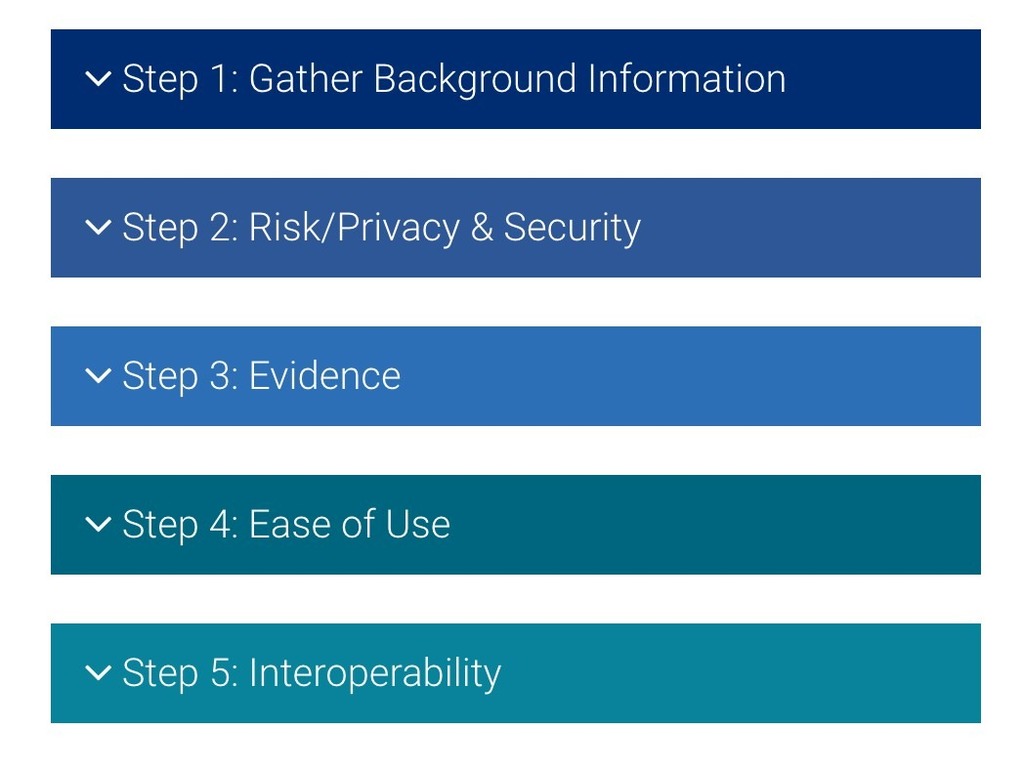

The American Psychiatric Association has formed a task force to study mental health apps and develop a framework to help healthcare professionals and consumers evaluate them. Torous chairs the work group. The hierarchical model guides people through a five-step decision tree. “We guide people to think about it and say, ‘If it meets your standards, move forward. If it doesn’t, you should probably not use the app,'” says Torous.

Ready for Disruption? Not Quite.

There is growing commercial interest in developing digital technologies for behavioral health. Alphabet, Google’s holding company, has hired top talent to lead the neuroscience team at Verily, including Tom Insel, former head of the National Institute of Mental Health. AngelList lists 307 mental health startups. “We’re seeing the interest is beginning to materialize in early products and research,” says Torous. “I don’t think anything is at this moment transforming or completely disrupting mental healthcare. I think it’s more realistic to say we are now learning about how all of these different tools work, and how they can be helpful.”

Jane Weber Brubaker is editor of eHealthcare Strategy & Trends.